FAQ¶

These are spontaneous answers to commonly asked questions, to make our next meeting more productive. Hopefully these will generate followup questions that we can take up during our interactions. Of course, opinions will evolve with time.

Raise¶

Why are you raising money now?

This is effectively our first formal raise, and the timing is quite deliberate and driven by three converging factors: product maturity, market validation, and commercial inflection.

In early 2024 we had initial conversations with a limited group of investors. At the time the market was focused on hardware demos, making “agentic infrastructure” for general-purpose robots, a difficult concept to communicate. Instead of forcing a premature narrative, we spent the last two years iterating on the system design. Today, EMOS has reached the “use surface”, transitioning from a technical project to a platform that delivers true app-style portability for Physical AI.

Moreover, our core assumptions about the industry have been validated by the broader market. Digital agents have become as foundational as systems of record (SORs). For robotics, pretty much all “AI labs” have a Physical AI effort going on. However, their efforts remain method-driven (trying to build models that solve fixed-scene manipulation). In contrast, we have stubbornly remained system-driven; we are building the orchestration environment that makes any model useful across any hardware.

At the same time, the rapid acceleration of hardware commoditization also changed the game. The influx of capable, low-cost general-purpose robots gave us a unique window to embed ourselves with OEM partners, studying their structural pain points and go-to-market struggles first-hand. This was a stress test for the design of EMOS that led to the addition of features specifically solving pain points that are now visible to the entire value chain.

Perhaps most importantly, we are raising now because we have successfully transitioned from a technical project to (at least an initial draft of) a commercial entity. We were adamant about not raising vanity capital to sustain a research effort. We wanted to lock-in a workable commercial model and land actual sales without falling into the “software consulting trap”. Having hit those milestones, we are now ready to scale both the technical and customer centric infrastructure that we believe will run the next generation general-robots.

What is the target raise?

We are raising a $750k – $1M Seed Round via standard convertible instruments (SAFE / BSA-AIR).

This is a rolling close designed to immediately bridge the gap between our successful field pilots and a high-scale commercial rollout. Having secured our first enterprise sale and distribution agreement, our goal for this capital is singular: to finalize the sales playbook and unit economics for EMOS. We aim to employ this capital for deployment-hardening and field-engineering, ensuring that our licensing model (15-30% of MSRP) scales effectively. This sets a clear path to reach the $500K+ ARR milestone by next year, putting us on a definitive trajectory for a major Series A in 2027. Furthermore, our intention is to onboard a select group of “champion” investors who can provide the strategic guidance required to popularize EMOS in the European market.

We have set the Valuation Cap at $6M.

This valuation reflects a fair entry point for our early strategic partners while acknowledging the value of an indispensable automation orchestration layer. Unlike “AI Labs” that require hundreds of millions in compute to show value, EMOS has already generated revenue on existing hardware. We believe this cap provides our early investors with significant upside as we move toward our $500K ARR target. Furthermore, by structuring this as a rolling round with standard instruments, we can onboard “champion” investors immediately, allowing us to stay lean and focused on field deployments rather than a prolonged fundraising cycle.

How do you intend to actually spend the money?

The capital will be allocated toward building a core team and popularizing EMOS, not just by community building around its OSS core, but through successful and high-visibility deployments. We believe we are now at the point of “context exhaustion”. An automation orchestration layer like EMOS requires the simultaneous management of multiple, deeply complex domains, navigation, cognitive reasoning and manipulation graphs, hardware abstraction, and user interaction. Our hiring philosophy is therefore built on absolute necessity. For example, the most urgent hires will be for the deployment context. We need testing and field engineers who can live between the code and the customer to ensure that the “last mile” of a security or inspection recipe is zero-friction.

By delegating these core contexts, we free ourselves to focus on the strategic expansion of the “Access Network”, negotiating the new OEM integrations and distributor partnerships. This spend is entirely focused on ensuring that by the time we hit our ARR goal, we have a team and a system that can support hundreds of robots in the field without constant manual intervention.

Competitive Moat¶

How do you compete with companies training Robot Foundation Models (e.g. Physical Intelligence or NVIDIA’s project Groot etc.)?

We don’t view companies training foundation models as competitors; we view them as essential partners in the ecosystem. Our recent collaboration with HuggingFace to integrate LeRobot policies into EMOS is a perfect example of this. These “AI Labs” are doing the vital work of solving the “method” problem, i.e. learning complex, non-linear manipulation tasks like folding laundry or picking up an object. However, there is a massive structural gap between a model that can perform an action on its designated embodiment and a robot that can complete a job in an unstructured dynamic environment.

Take the example of a robot tasked with loco-manipulation of opening a door. A foundation model (VLA) might excel at the dexterous part, the grasp and the turn. But in a real-world application, that model is effectively a “stateless” tool. It doesn’t know which door is the right one, how to navigate to it safely through a crowded hallway, or what to do if the inference server lags. Most importantly, it doesn’t know when to trigger itself. Without a system-level runtime, these models require a human in the loop to “press play” for every specific sub-task. If the robot gets stuck or the environment changes mid-action, the model simply breaks because it lacks the broader context of the mission.

EMOS provides the missing decision architecture that turns these models into autonomous agents. While the AI Lab focuses on the specific neural network, EMOS handles the actual runtime. It manages the semantic memory (remembering where the door is), state-of-the-art navigation (to navigate through a crowded hallway of dynamic obstacles), the event-action logic (detecting that the robot is now close enough to attempt an opening), and the safe execution of manipulation control commands (control thresholding and smoothing based on joint limits). And all of this while remaining robot agnostic and serving an interaction UI.

Even under the most techno-optimist scenario that ALL physical world variations can be encoded in the training data or test-time learning would reach human level efficiency, EMOS would remain absolutely essential and would include parts of the technology stack that are currently not being worked on by AI labs. We aren’t trying to win the race for the best robot brain (whatever that means); we are building the cortical structure that allows any effective model to be deployed, orchestrated, and scaled across different hardware platforms.

What is your moat against companies making robots?

The reason OEMs struggle to build an orchestration layer like EMOS is the same reason why Android wasn’t built by a phone manufacturer and Windows wasn’t built by a PC maker. There is a fundamental conflict of interest between making a general-purpose physical machine and building the horizontal ecosystem that makes that machine useful.

The DNA of a hardware company is fundamentally geared toward the physical. To an OEM, software is often viewed as a “support feature” for the bill of materials, whereas for us, the software is the product. Robot OEMs already have to grapple with locomotion control, the balance and the gait, which are big engineering hurdles but ultimately localized to the machine. Building a Physical AI runtime requires managing high-level cognitive contexts and event-driven adaptivity in the external world of the actual use-surface, tasks that are culturally and technically alien to a manufacturing-heavy organization. Furthermore, when a hardware manufacturer builds software, their primary incentive is to lock users into their specific chassis. If an OEM were to build a high-level OS (Agibot already has such an ongoing project), they would never optimize it to run on a competitor’s hardware. This fragmentation is exactly what kills mass adoption. OEMs doing manufacturing at scale and keeping other costs low would automatically gain a competitive advantage over rivals, if a robot agnostic orchestration layer is freely available, built by specialists and taking into account the subtleties of actual use-case deployments.

We are building universal primitives that apply to every general-purpose robot on the market. By providing the missing orchestration layer, we allow the hardware to become a liquid asset, moving the industry away from custom research projects and toward the standardized, deployable era of Physical AI.

Can’t someone build a system similar to EMOS just by using a collection of ROS packages?

It is a fair question, but it stems from a common misconception: ROS is actually a middleware, the plumbing, not a robot OS in the functional sense. The open-source community has developed excellent specific capabilities, written in the standard language of ROS, like mapping or point-cloud processing, but these are isolated tools, not a unified runtime.

The most critical missing link in the standard ROS ecosystem is system behavior. Historically, ROS graph definitions have been rigid and declarative, designed for robots that perform a single, pre-defined task throughout their lifecycle. They lack a native way to react to the unstructured world, like knowing how to gracefully reallocate compute when a battery runs low, or how to swap a vision model in real-time when lighting conditions change. EMOS provides the industry’s first event-driven architecture that orchestrates these system-wide behaviors. It moves the developer away from writing fragile, custom state machines for every new deployment and toward a beautiful, imperative API where adaptability primitives, like Events, Actions, and Fallbacks, are fundamental building blocks.

Furthermore, EMOS solves the “project vs. app” problem. In the traditional ROS world, every new robot deployment is a bespoke R&D project, a brittle patchwork of launch files that are notoriously difficult to reuse. EMOS introduces the concept of Recipes: hardware-agnostic application packages, which are a combination of functional primitives that wrap ML and control algorithms. Furthermore, many of these functional primitives are completely unique to EMOS and state-of-the-art, thus not even available in the broader ROS ecosystem.

Finally, there is the issue of production-grade stability. Anyone who has managed a robot deployment knows that stitched-together ROS packages are incredibly brittle. EMOS is a bundled, validated runtime. By providing a single source of truth that defines everything from the logic to the auto-generated interaction UI, we reduce the development cycle from months of custom engineering to hours of recipe development and configuration. The bulk of the time spent by the developer should be on real-world testing and validation.

Why is GPGPU Acceleration in navigation a differentiator? Can’t one just use a faster CPU?

In the current robotics landscape, GPU acceleration is almost exclusively relegated to the perception pipeline, handling heavy image processing or ML application, while the actual navigation and control logic remains bottlenecked on the CPU. Kompass is the first navigation stack in the world to explicitly provide GPGPU kernels for these core navigation components. The performance gap is not a matter of incremental gain; it is a difference of several orders of magnitude that a faster CPU simply cannot bridge.

Most robotics control software was written for a world with small embedded platforms with little to no integrated GPU availability. NVIDIA Jetson changed that and has become a standard now. More players offering smarter and cheaper compute options will enter this market (and we intend to encourage them).

Our benchmarking results clearly demonstrate this divide. For complex motion planning tasks like the cost evaluation of candidate paths, which involves a massive parallel rollout of upto 5,000 trajectories, a standard embedded CPU (like the RK3588) takes nearly 28 seconds to compute a solution. In a dynamic environment, this latency makes state-of-the-art autonomous navigation impossible. By utilizing GPGPU kernels, the same task is completed in just 8.23 milliseconds on an accelerator, a 3,106x speedup. Similarly, dense occupancy grid mapping sees a 1,850x speedup, turning a 128ms CPU bottleneck into a sub-millisecond background task. This level of throughput allows for a degree of reactivity and situational awareness that traditional CPU-bound stacks, like Nav2, fundamentally cannot achieve.

Beyond raw speed, the differentiator is one of efficiency and flexibility. Kompass is built on GPGPU primitives (SYCL), meaning it is entirely vendor-neutral and breaks the traditional hardware lock-in. Whether an OEM chooses NVIDIA, AMD, or even upcoming NPU-heavy architectures that have an integrated GPU, the same navigation logic runs optimally without code changes. Our efficiency benchmarks show that GPGPU execution is significantly more power-efficient, offering vastly higher Operations per Joule compared to CPU baselines. This is critical for battery-powered mobile robots where every watt saved on compute is a watt spent on mission duration.

For hardware platforms without a dedicated GPU, Kompass doesn’t just fall back to legacy performance; it automatically implements process-level parallelism to optimize algorithm execution far beyond native CPU performance. We have built Kompass so that control intelligence is never constrained by compute architecture and a developer is free to assign CPU or GPU compute to various parts of the stack based on execution priority.

You can see the full breakdown of these performance gains here

Safety, Reliability & Scalability¶

AI is known to hallucinate, why would one want to use LLMs/VLMs in real world deployments?

The concern regarding hallucinations is valid when viewing AI as a black box generating free-form text, but in EMOS, we treat LLMs and VLMs as modular reasoning engines within a strictly defined agentic graph. The key to reliability in real-world deployment is not trying to eliminate hallucination entirely within the model, but rather building a system-level architecture that enforces determinism through several layers of validation.

First, one can utilize structured output and post-processing. Instead of dealing with raw text input/output, both LLM and VLM components in EMOS can consume and produce structured data via templated prompts and schema-driven constraints. One can then pass all outputs through arbitrary post-processing functions that validate the it, against the robot’s current physical reality. If a model suggests an action (for example an unrealistic goal-point) that violates safety constraints or logical schemas, the post-processing function can identify the hallucination as a data-type or logic error and which can be used to trigger a recovery routine.

Second, both LLM and VLM components do not execute actions directly; they can however, call “tools” which are essentially deterministic functions in other components, or supplied by the user in the recipe. For example, an LLM that parses user’s spoken intent in a recipe doesn’t just say “move forward”; it triggers a specific action server in Kompass with a goal-point, that handles the actual obstacle avoidance and path planning using GPGPU-accelerated control algorithms. This effectively walls off the hallucination-prone reasoning from the “safety-critical” execution.

Why do you build on ROS? Doesn’t that create a lock-in for you?

Choosing to build on ROS is a strategic decision based on the current reality of the robotics market. ROS is the undisputed lingua franca of the industry, and building on it ensures that EMOS has immediate, out-of-the-box compatibility with the vast ecosystem of existing hardware drivers, sensor suites, and community-vetted tools. However, there is a fundamental difference between utilizing a standard and being trapped by it. We have architected EMOS specifically to ensure that we are never “locked in” to any single middleware.

The primary defense against lock-in is that our core architecture layer is decoupled from any middleware-specific logic. We view the middleware as merely the transport layer for data and a launch system for processes. To bridge this core logic to the outside world, we developed a proprietary meta-framework called Sugarcoat. Sugarcoat acts as an abstraction layer that translates our internal nodes, events, and communication pipes into ROS2 primitives, using rclcpp. Today, we use it to talk in ROS2 because that is what our customers and OEM partners require to make their robots functional.

Tomorrow, the industry may shift toward newer, high-performance alternatives like ROSZ or dora-rs for better memory safety and lower latency (they are currently experimental). Because of our architecture, a transition would not require a rewrite of EMOS. We would simply update the Sugarcoat backend, and the entire EMOS stack, including all existing “Recipes”, would migrate to the new middleware instantly. This approach allows us to enjoy the ecosystem benefits of ROS today while maintaining the agility to adopt whatever plumbing the future of Physical AI demands.

What is your data strategy, and how do you actually utilize the information coming off robots in the field?

Our data strategy is built on a fundamental fact: unlike LLMs, Physical AI does not have its internet scale datasets. You can use simulation to bridge the gap but building high-fidelity simulations with sim-to-real generalization is a challenge on its own. A lot more real-world data collection setups are required to teach ML based controllers how to navigate a particular cluttered basement or manipulate a custom industrial valve. This is why we focus on capturing the “Access Network”. By having EMOS deployed on real-world robots, we aren’t just providing a “second-development” platform. We are creating a distributed sensor network that generates high-fidelity, context-specific data that simply doesn’t exist anywhere else.

There is an additional advantage with EMOS. The user is not restricted to use the vacuum cleaner approach to data collection, where you dump terabytes of raw video and language instructions and hope for the best. Instead, the EMOS event-driven architecture can be used to trigger surgical extraction. Through our partnership with players like Heex Technologies, we can configure a robot to only save and upload data from user-specified components when something “interesting” happens, like a navigation fallback, an environmental trigger, or a manual intervention by a human operator. This allows the user to build a library of edge cases that are the “gold” for model retraining, without the overhead of massive, redundant data logging.

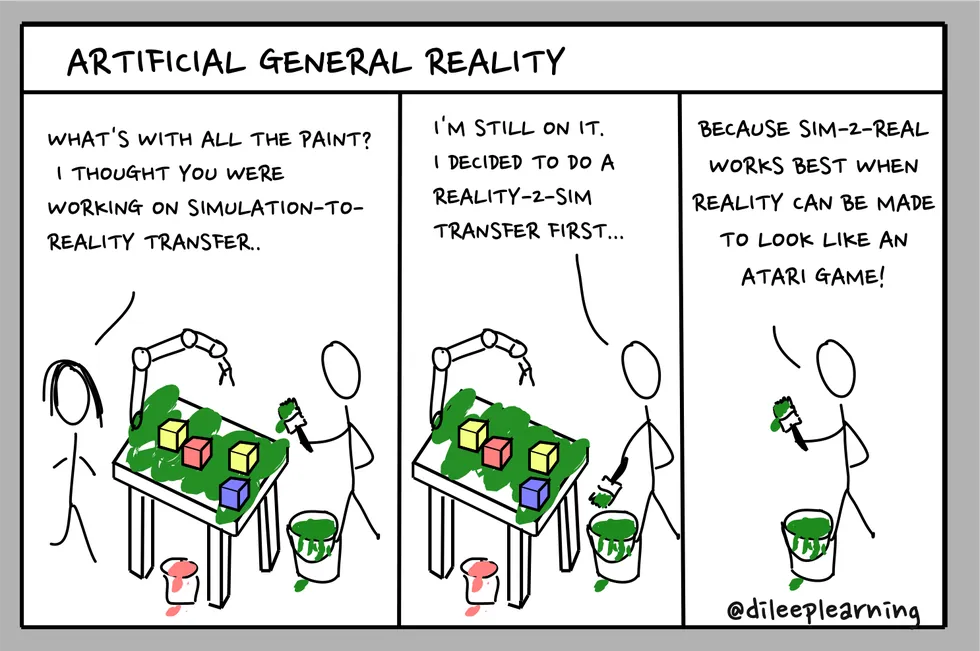

Sim-to-Real “strategy”. Credit: AGI Comics by @dileeplearning.¶

Commercialization & Business Model¶

What is your business model? Or as one visionary Gentleman VC put it in early 2024, “So, you intend to make software for “cheap” Chinese robots, how will that work?”

We operate on an Open Core and OEM Partnership model, similar to the strategy Canonical uses for Ubuntu, making it a major player in cloud infrastructure and desktop. The goal is to make the EMOS orchestration layer ubiquitous by providing an open foundation, while monetizing the enterprise-grade reliability and deployment infrastructure required for the last mile of industrial automation.

This strategy essentially turns the traditional robotics sales cycle on its head. Instead of chasing one-off consulting projects, we partner with hardware OEMs and distributors to pre-install EMOS at the factory level. This bundling ensures that when a robot reaches an end-user, it is already ready to run. For the OEM, this solves the problem of their hardware sitting idle due to poor default software; for us, it captures the “Access Network” by ensuring EMOS is the substrate for every application built on that machine.

We monetize through Value-Based Commercial Licensing, where our license fees are pegged to the hardware’s capability, typically between 15% and 30% of the MSRP. Our paid tiers provide the professional-grade support, deployment-hardening reports, and any 3rd party integration hooks, that are strictly necessary for production environments. This model allows us to benefit from the ongoing commoditization of hardware; as robots get cheaper and more capable, the demand for a standardized, reliable orchestration layer like EMOS only grows.

The “Open Core” itself is a deliberate play for ecosystem velocity. By keeping the primary components under the MIT license, we ensure that students, researchers, hobbyists and most importantly, AI agents, can build on EMOS for free. This builds a global talent pool of “Robot Managers” who are already fluent in our API before they ever step into a commercial environment. When these developers are eventually tasked with deploying a fleet of security or inspection robots, EMOS becomes the path of least resistance.

Won’t robot manufacturers prefer to build their own software stack in-house?

This question was already answered above but lets answer it again with a different argument.

This mindset is a vestige of the era of single-purpose automation. In the old paradigm, where a robot was built as a “Tool” solely to perform a fixed task in a static environment, like a robotic arm painting a car door on an assembly line, vertical integration made perfect sense. When the scope is narrow and the hardware never changes its mission, you can afford to hard-code every interaction. But we are now entering the era of the “Robot as a Platform”. Modern robots, particularly the quadrupeds and humanoids hitting the market today, are general-purpose machines meant to run multiple applications. A single robot might be expected to perform a site inspection in the morning, act as a security sentinel at night, and serve as a delivery mule in between.

For an OEM to build a software stack that can handle this level of versatility is a massive, often terminal, R&D burden. Building the robot hardware through an elaborate supply chain, while managing GPGPU-accelerated navigation, complex ML model orchestration, real-time event handling adaptability, and a hardware abstraction layer all at once is what one can call undifferentiated heavy lifting. By adopting EMOS, OEMs can effectively skip this software burden and ship a machine that is “intelligent” on day one. It allows them to participate in a virtuous cycle: as software becomes a commoditized, platform-agnostic layer, the cost of bringing a new robot to market drops, while its immediate utility to the end-user skyrockets. We aren’t competing with the manufacturers; we are giving them the tools to stop being research projects and start being viable commercial products. Just as Dell or Samsung didn’t need to write their own operating systems to dominate their markets, the winners in such a general-robotics market will be the ones who focus on their machines and leave the orchestration to a standardized runtime.

Is EMOS exclusively for complex, general-purpose robots like humanoids? Does it have a play in the single-function robot market?

The answer to the first question is, most definitely NOT. While our presentation highlights quadrupeds and humanoids, EMOS is fundamentally robot-agnostic. Whether a robot has two legs, four legs, or four wheels or it flies in the air, the orchestration challenge remains the same.

The reason we focus on general-purpose robots (platforms) is simple: we want to showcase the “Autonomy as an App” model. General-purpose robots are the most complete and complex platforms to demonstrate this. They allow us to bundle EMOS as commodity software that acts as the universal runtime for these “apps”.

EMOS is, in fact, a cheat code for single-function, specialized robots. Because a specialized robot; lets say, a hospital delivery cart, requires 90% of the same infrastructure layer:

Safe, reactive navigation in a human-populated environment (Kompass).

Sensor fusion and ML perception (EmbodiedAgents).

Operational state management and event-handling, including the ability to call external APIs.

A professional UI for the human operators that integrates with 3rd-party systems.

Without EMOS, developers spend months stitching together ROS packages and custom code. With EMOS, they write one Recipe and test it in a few days. We turn a year-long R&D project into a weekend configuration task and add a whole host of new capabilities out-of-the-box for developers to enhance the robot’s interactive capabilities.

Providing EMOS as a horizontal infrastructure layer follows the pattern Applied Intuition proved in the automotive world. Applied Intuition provided the tools for car companies to build their own automation stacks. EMOS is that horizontal layer for the broader robotics market, already primed for diverse, unstructured and dynamic environments that these robots have to operate in.

As hardware commoditizes, OEMs of single-function robots (like retail inventory robots or mining vehicles) will face price competition, making vertical integration unsustainable. By adopting EMOS, they get a “white-box” solution that includes the actual navigation and intelligence stack, letting them compete with the best without the crushing R&D burden.

Consider a pizza delivery bot startup. Currently, it has to build the chassis, the autonomy stack, and the logistics network. In the future, they will buy a commoditized chassis, load EMOS for the managed autonomy layer, and focus 100% of their effort on the service (the pizza delivery App). We intend to enter these markets and sell Service-Driven Licenses directly to these fleet operators, effectively becoming the infrastructure for Physical AI: you run your business logic on top, and we handle the complex reality of keeping the robot moving.

Intellectual Property & Strategy¶

As a spin-off from a research lab, who owns your IP?

Automatika Robotics has full ownership of its IP.

Why doesn’t Automatika have any filed patents yet?

The short answer is that we are limited by resources and had to choose between filing paperwork and shipping a working system. We chose the latter. Up until now, our focus has been on proving that our Physical AI orchestration layer actually works in real-world environments. However, our strategy was never to ignore IP, but to prioritize defensive publication. By open-sourcing the core of EMOS, we have effectively created a public record that prevents anyone else from patenting the fundamental layers of our architecture.

That said, we have identified high-value innovation families in our work (e.g. our proprietary GPGPU navigation control kernels in Kompass and our self-referential graph adaptivity logic). Establishing a formal patent portfolio for these specific innovations is a core milestone for this funding round.

How do you intend to protect yourself against patent trolls in the robotics space?

Our protection strategy is a two-layered defense built on “Prior Art” and institutional support. By aggressively documenting and open-sourcing our core components, Kompass, EmbodiedAgents, and Sugarcoat, we have established a massive public record footprint. In the patent world, this should act as a poison pill for any trolls; it is very difficult to sue someone for inventing a concept that they have already publicly documented and released under an MIT license years prior.

As we scale and formalize our IP, we also intend to join defensive patent pools and cross-licensing networks, much like the Open Invention Network (OIN) did for the Linux ecosystem. Furthermore, our roots as an Inria spin-off provide us with an academic shield. We have access to decades of institutional prior art and research data that can be used to invalidate overly broad or frivolous patent claims.